Martin Sheen and a romantic military trope explain corporate reality

Harvard Business School graduates consider themselves extremely entitled. Or so the reputation goes.

Yet the same is said of millennials or, for that matter, the average recent college graduate.

But is there a greater sense of entitlement as generations issue forth from wombs — and then schools — inexorably over time? Maybe. But Elbert Hubbard apparently thought entitlement was already at its peak when he wrote “A Message to Garcia” — back in 1899(!).

Hubbard’s famous essay is de rigeur for new entrants, “plebes,” at the U.S. Naval Academy, wherefrom this author graduated. The story itself is a kind of one-line refrain spoken occasionally among servicemembers, setting a foundation for the way in which military officers think about leadership. Though it is telling that the story is used more often in jest and cynicism than in serious discourse.

If you’ve never read it, put on your best robber-baron monocle, picture late-19th century geopolitics, and give it a try (free PDF).

In “A Message to Garcia” we see Army 1st Lieutenant Rowan tapped by U.S. President William McKinley to take an important dispatch to Cuban insurgent General Calixto García: “somewhere […] no one knew where.” Supposedly our hero asked no questions despite what by any measure both then and now was a completely vague and open-ended ask. Rowan became an example both intrepid and dutiful, cited widely by leaders of every kind.

A young person in her early training can feel an immense feeling of empowerment, trust, and impact upon first hearing the story. Because on its face Hubbard’s famous essay is primarily about initiative.

And that’s the narrative spun by the scrupulous minders of young military minds. But closer inspection reveals a desire more for fealty than agency.[1]

Setting the record straight

No account of the core story in “A Message to Garcia” would be complete without clearly acknowledging its falsehood. I discuss many of the fabrications by the essay’s author as well as his ‘lies by omission’ in my podcast episode on the topic. But to illustrate the degree to which the story itself was contorted to serve the purposes of Hubbard, I can’t do any better than this quote from Wikipedia:

In fact, the only true statement Hubbard wrote was that Rowan “landed … off the coast of Cuba from an open boat”. All the rest, including McKinley’s need to communicate with Garcia and Rowan’s delivery of a letter to the general, was false. [emphasis added]

But even a purely fictional story can have practical, even moral, value. One could ask herself, would I be willing to take such a mission? In this case, the task is not only vague and complex, but the situation is dynamic and path-dependent. In other words, people may react to your moves, and your first steps will heavily influence later possibilities. Such a mission would require bravery, adventurousness, and self-confidence that one will figure out each part of ‘the how’ in its right time.

Mission focus and problem solving are the real message we can take away from “A Message to Garcia” — even though most of the story was a lie.

The real lesson

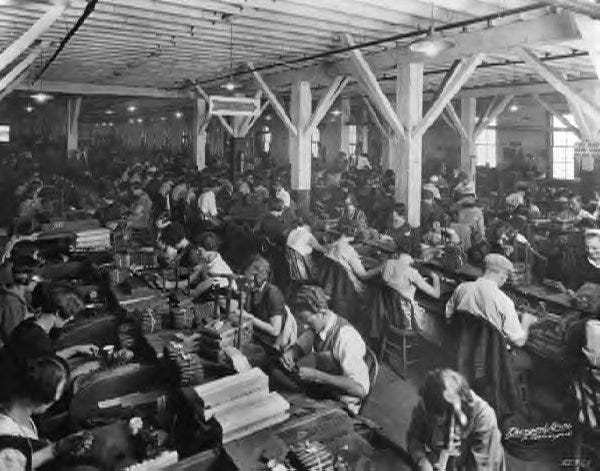

There is a trope: “You don’t get paid to think.” It’s so overused in pop culture, but it also sounds antiquated, like a refrain that late-1800s factory workers might hear. So it is easily forgotten or dismissed.

Besides, no company today would permit a manager to say such things, since such a quote would repel the highly educated and ambitious people who solve the hard problems that create so much value for business.

Above I recommended dressing up like Mr. Monopoly before reading the essay, because the tone has a distinctly Napoleon Hill feel to it.

It is generally condescending toward the working class and posits a ridiculous example to show how the average clerk might question orders.[2] Of course, the mere fact that both this new hypothetical example and the core story about Rowan and Garcia depict workers following orders demonstrates how the essay is not about initiative at all.

You, reader, put this matter to a test: You are sitting now in your office — six clerks are within your call. Summon any one and make this request: “Please look in the encyclopedia and make a brief memorandum for me concerning the life of Corregio.” Will the clerk quietly say, “Yes, sir,” and go do the task? On your life, he will not. He will look at you out of a fishy eye,

Hubbard doubles down on his rant, insisting that extreme threats are needed to keep workers in line. I agree to some extent that fear is why most people show up to work, but Hubbard goes too far:

A first mate with knotted club seems necessary; and the dread of getting “the bounce” Saturday night holds many a worker in his place.[3]

And again…

He is impervious to reason, and the only thing that can impress him is the toe of a thick-soled №9 boot.

Just. Wow.

What Elbert Hubbard is seeking is discipline. Unthinking subservience. Unswerving loyalty.

If Hubbard had served in the military, he would realize that the service is more like Catch-22 than it might appear. Ridiculous demands abound. And a leader has an obligation to serve the country and the mission more than his superior.

One key feature of the military is that its members take that obligation seriously; whereas, in my experience it is seldom the case in the private sector that a manager care about anything except not disappointing his boss. The point is that sometimes, maybe often, it makes sense to question orders.

Question, with extreme prejudice.

Thinking vs. thought

Knowledge workers early in their careers may comfort themselves with the notion that so much of their job is mental. They are paid to think.

There is a difference, though, between exercising brainpower (thinking) — and pure, free thought.

Smart people, especially ones who buy into the mission, often delude themselves into thinking that they really are paid to think — and to achieve the mission; neither could be farther from the truth. In reality in most companies you are paid to please your boss. That’s it.

Except in the rarest of startups (or perhaps nonprofits), you’re generally paid to be a servant. Don’t let your t-shirt and jeans attire, free cappuccinos, and catered lunch on Fridays fool you. You’re an overpaid butler.

People who think lead independent lives. They are writers, artists, and entrepreneurs. Or they are miserable.

Collecting a paycheck doesn’t really mean surrendering your hours or your work. It means surrendering your mind, dignity, beliefs, and desires.

So if people seem entitled more and more, perhaps it’s just that they simply have a desire to remain an individual, dignified human.

Corporation Now

If you have the capacity to think expansively and work inside a big company, then you are cursed. Things will happen around you that will force you to think. Your mind can’t help it. Decisions will be made, external forces will be applied, and entropy will work its dark magic. The “little gray cells,” as Hercule Poirot would say, will toil, and trouble shall follow.

All the way wet (aka footnotes)

[1] Bots are all around us. Elbert Hubbard might want you to be a computer player, too. (The Warrior Poet — Episode #9: Ready Player One)

Separately, agency is an interesting concept philosophically and sociologically.

[2] Lots of clerks back then lol. We can assume they were the earliest non-executive knowledge worker.

[3] Most people worked 6–7 days per week back then, so a Saturday night firing would be equivalent to today’s usual habit of terminating people on Friday afternoons.

Aside from Wikipedia

Thought this detail on Hubbard was interesting. I had assumed he would have been more of a religious conservative.

Hubbard wrote a critique of war, law and government in the booklet Jesus Was An Anarchist (1910). Originally published as The Better Part in A Message to Garcia and Thirteen Other Things, Ernest Howard Crosby described Hubbard’s essay as “The best thing Elbert ever wrote.” [Wikipedia footnote omitted for clarity]

About the author: Sri hosts The Warrior Poet podcast, a show on the philosophy of leadership based on his experience in the SEAL Teams, at Harvard Business School, on Wall Street, and in tech. Shows every Monday. Follow him on Instagram @sri_the_warrior_poet.

Recent Comments